Introduction: The Button That Refused to Work

I wasn’t trying to reinvent anything. I was just experimenting.

While playing with a tiny React component—a button that updates a greeting—I hit a wall. My code compiled without issues, the console logs seemed fine, but the UI refused to update. Clicking the button did nothing. No error. No warning. Just… stasis.

I’ve debugged more complex problems before. But this felt personal: why wasn’t my basic state update working?

That one bug turned into a multi-hour exploration into how React handles state, the pitfalls of object mutation, and why immutability isn’t just a clean coding practice—it’s the backbone of React’s rendering strategy.

What’s Happening Under the Hood?

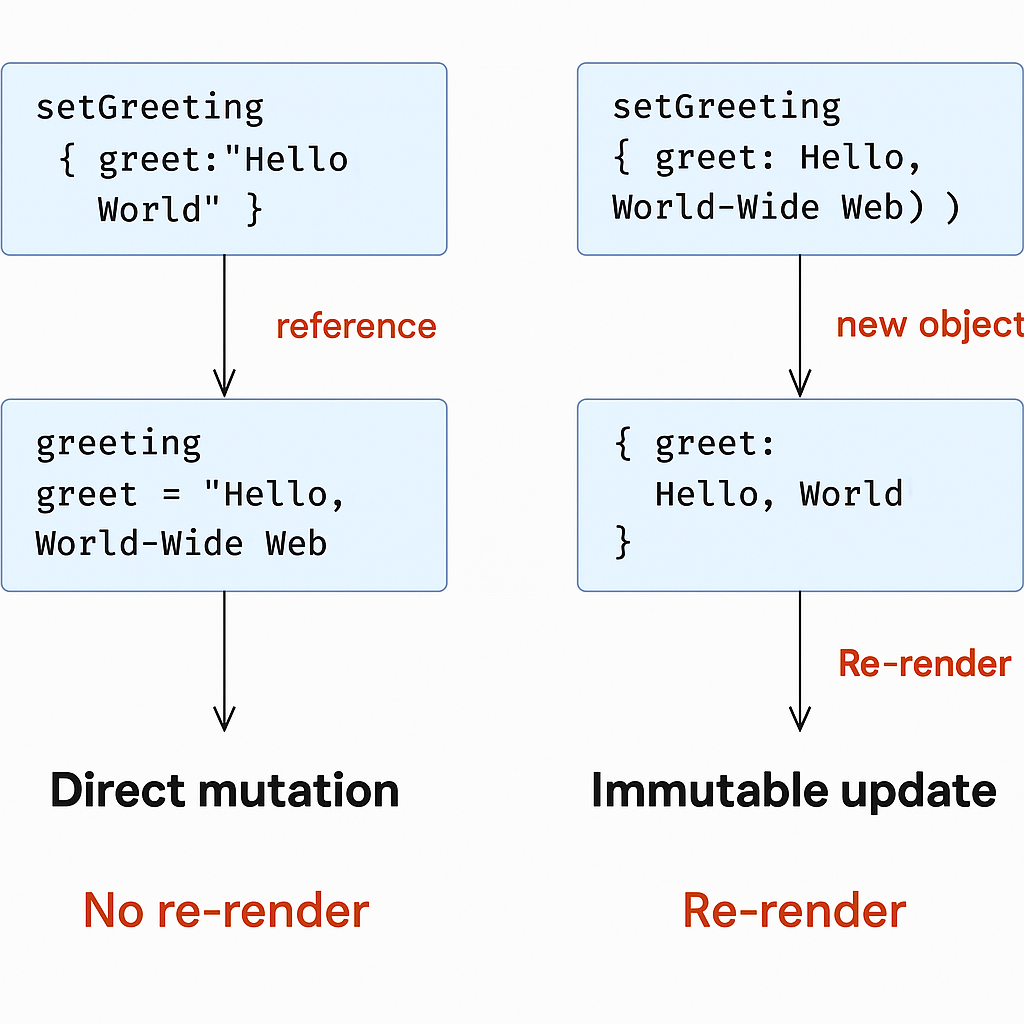

To understand why my component failed silently, I had to rewire how I thought about state. React doesn’t re-render because you changed something. It re-renders because it detects a change—and detection depends on reference identity.

Let’s break this down:

🧩 React’s state change detection logic

React uses shallow reference equality when comparing state values. If you call setState() with an object that has the same memory reference as before—even if its internal values changed—React assumes there’s nothing new to render.

Here’s what I did wrong:

greeting.greet = "Hello, World-Wide Web"; // ❌ mutated original state

setGreeting(greeting); // ❌ same object reference

React looked at the greeting object before and after the update and said:

“This is the same thing. I’m not re-rendering anything.”

And honestly? It’s kind of beautiful. React is efficient by design—leaning on object identity to avoid unnecessary DOM work. But if you don’t provide a new reference, you’ve effectively jammed the signal line.

🔍 Why React behaves this way

This behavior is tightly coupled to performance. Instead of deep comparison (which is expensive), React relies on quick reference checks (===)—especially during reconciliation in the virtual DOM.

That’s why immutable updates are so important. They act as a clear signal:

- “Hey React, here’s a new object—check it out.”

- React sees the change and re-renders accordingly.

Code Scenarios: What Works vs What Doesn’t

| Code Pattern | Behavior | Works? |

|---|---|---|

greeting.greet = "new" then setGreeting(greeting) | Mutates original object | ❌ UI does NOT update |

setGreeting({ greet: "new" }) | Creates new object | ✅ UI updates |

const newGreeting = { ...greeting }; newGreeting.greet = "new"; setGreeting(newGreeting); | New reference | ✅ UI updates |

setGreeting(prev => ({ ...prev, greet: "new" })) | Functional update | ✅ UI updates |

greeting = { greet: "new" } | Illegal in const declaration | ❌ Throws error |

greeting.greet = "new" (no setGreeting) | Mutates in memory only | ❌ No UI update |

setGreeting(greeting) after mutating nested property | Same reference | ❌ No re-render |

Why Immutability Isn’t Just Dogma—It’s a Performance Strategy

For a long time, I thought immutability was just good hygiene—something you do to avoid side effects. But inside React, it’s not just a preference—it’s a performance feature.

⚡ Immutability enables:

- Efficient reconciliation with quick reference checks

- Memoization with

useMemoandReact.memo - Debug-friendly snapshots of previous state

- Optimized rendering with fine-grained control

If React had to deeply compare nested objects every time, the rendering engine would crawl.

Creating a new object with each update ensures:

“Hey React, something changed—come take a look.”

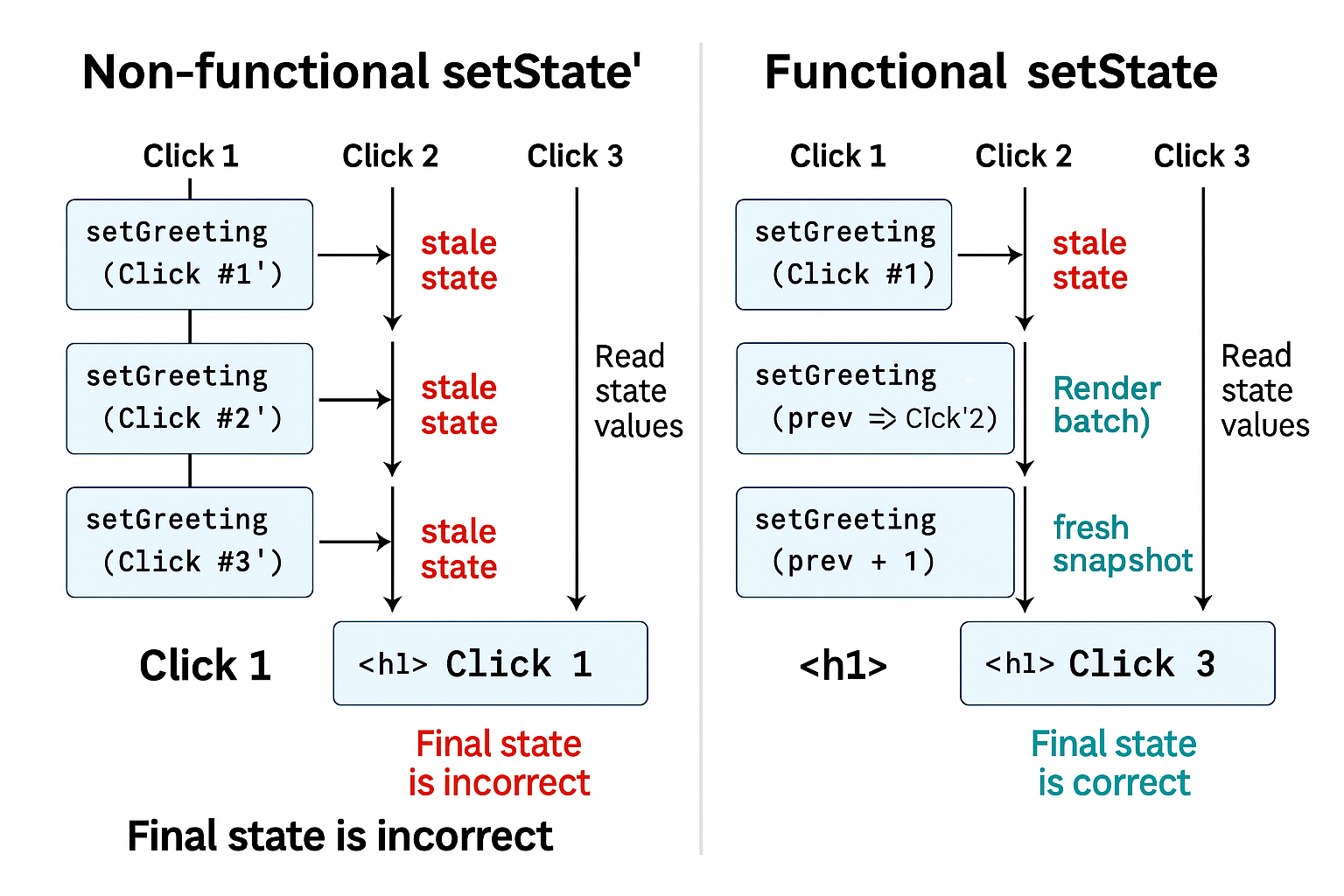

Functional Updates: Surviving React’s Rendering Storm

Once I embraced React’s functional update syntax, everything clicked:

setGreeting(prev => ({ ...prev, place: "World-Wide Web" }));

React 18 introduced concurrent rendering features that batch or delay updates. This means traditional updates like setGreeting(greeting) may not reference the latest state by the time they execute. And this is an important thing to note, as you can simply tackle ‘avoidable’ mistakes!

Functional updates solve this by:

- Pulling the latest state snapshot at runtime

- Ensuring atomic and composable updates

- Avoiding race conditions or stale closures

Especially when handling complex forms or chained updates, functional patterns are more resilient.

🧪 Real-World Use Cases for These Techniques

Feature | Why Immutability + Functional Updates Matter |

|---|---|

| Redux reducers | Enforces predictable state transitions |

useMemo and React.memo | Avoids re-renders via reference checks |

| Concurrent rendering | Prevents bugs caused by stale state |

| Optimizing parent-child props | Avoids unnecessary rendering of child components |

| Complex form state | Enables targeted updates with clarity |

Wrapping Up: The UI That Finally Worked

Here’s the version that felt like magic—not because it did something fancy, but because it finally aligned with React’s mental model:

import { useState } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [greeting, setGreeting] = useState({ greet: "Hello", place: "World" });

function updateGreeting() {

setGreeting(prev => ({ ...prev, place: "World-Wide Web" }));

}

return (

<div>

<h1>{greeting.greet}, {greeting.place}</h1>

<button onClick={updateGreeting}>Update greeting</button>

</div>

);

}The key here is combining immutability (via spread syntax) with a functional updater. It’s readable, declarative, and fully reactive.

This simple refactor reflects a deeper shift in how I think about UI: every change is a signal. And React only listens if you speak its language.

🔥 Final Reflection: Learning React’s Language

That bug wasn’t just annoying—it was instructive.

It taught me that in declarative UI, the “what” is less important than the “how”. React’s internal elegance is built on assumptions:

- State must be immutable.

- Updates must be explicit.

- Signals must be clear.

Once you respect those principles, the framework rewards you with beautiful, predictable UI.

If you’re debugging silent failures, look beyond your values. Look at your references.

Immutability isn’t just a style. It’s the syntax of reactivity.